Special Relativity with Geometric Algebra - Spacetime Algebra

Paths of objects

There are different ways to understand and formalize the paths objects take and how they move over time.

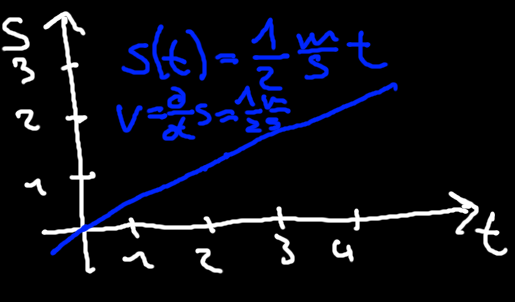

Position over time

In physics we often draw the path an object takes over time in a diagram where time is on the x-axis and space is on the y-axis. Figure 1 shows such a diagram. For an object with a constant velocity of one half meters per second we have the following equations

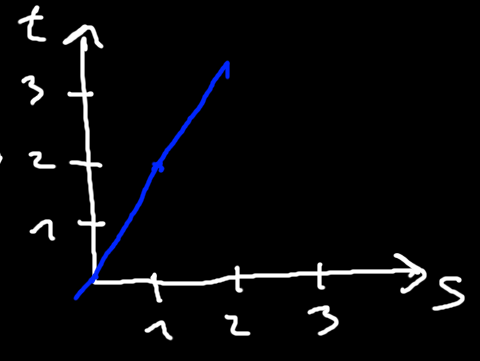

Position over time - flipped space and time axes

In relativity, the space and time axes are usually flipped, so we space is on the x-axis and time is on the y-axis. We will also follow this standard practice. Doing this our diagram will look like this

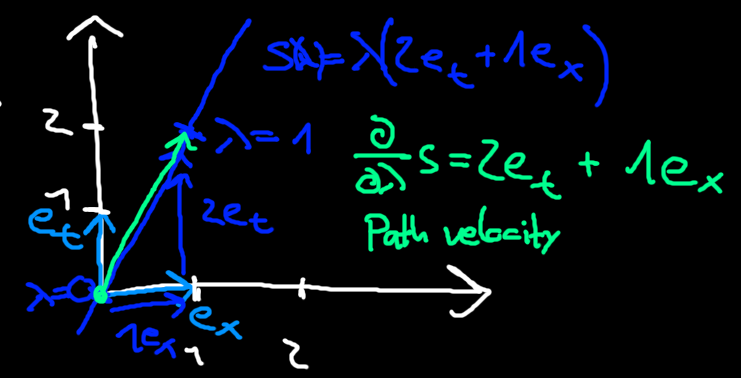

Since we are using geometric algebra, we will use vectors to formulate paths of objects instead. We will have the usual spatial basis vectors

Parameterized paths with vectors

For our previous example, for every step in the space direction we take two steps in the time direction. So an unnormalized direction vector for the path is given by

We can also calculate a path velocity by taking the derivative with respect to our path parameter

The path velocity is always tangent to the path.

Note that the parameterization for our path is somewhat arbitrary. We could just as well have multiplied by path by a constant and have gotten the same path. What happens to the path velocity when we multiply our path by a constant factor

The path velocity also receives the constant factor

Our path parameterized by proper time is then

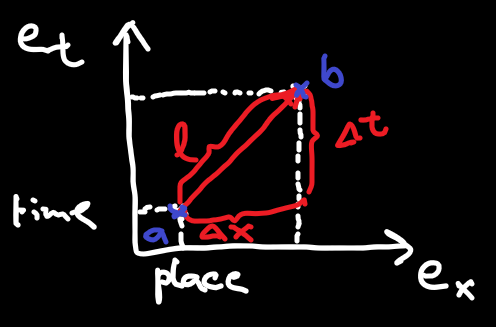

Spacetime events

Another thing we want to look at is what the points in our spacetime, such as the points on our paths, represent. A point contains a time coordinate and three space coordinates. Points in spacetime are also called events because of this.

An event

Does this expression make sense? The first problem we can notice is that the units don't match up. How do we add kilometers (spatial distance) and seconds (time difference)? To remedy this, we could multiply the time component by a constant speed as that would result in a distance. Why not choose the speed of light

Well we got around the unit issue, although we did not justify the multiplication by

More spacetime paths

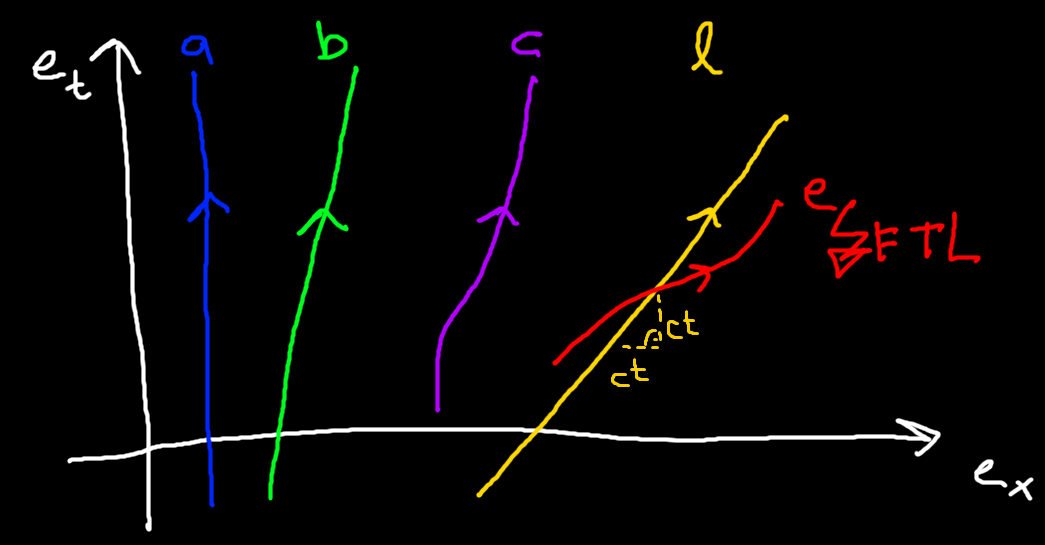

Let's take a look at some more types of paths in spacetime.

Object at rest (a)

An object at rest does not move in space over time. Its path points purely in the time direction. The path can of course still be arbitrarily offset on the space axes.

The path velocity always points in the

Object with constant velocity (b)

Objects with constant velocity can move in space. Their path will be a rotated straight line. The more rotated the line is towards the space dimension, the faster the object goes.

The path velocity for an object moving along the x-direction will be some mix of

Object with acceleration (c)

An object with acceleration could trace out a curved path like

Light (l)

Light always moves at the speed of light. This is the second postulate of Special Relativity. Its path can be parameterized by

Faster than light (e)

Because nothing can move faster than light, this means all of our paths need to be steeper than 45°. Otherwise the object would be going faster than light.

Spacetime distance

Something we have not looked at yet is what a good notion of distance in spacetime is. Squaring vectors gives us vector lengths. When we do this, we make use of the squares of basis vectors. What should our spacetime basis vectors square to? To figure this out will perform a thought experiment involving light clocks and trains.

Light clocks and trains

First of all there are great videos demonstrating what we're about to investigate. You might want to watch them first or watch them if you get confused about the writing, the videos do a much better job. For example this one (although they put the device on the train instead of outside of it). We won't be using mirrors here as we can get the same result without two trips which also simplifies the math a bit.

Video 1 - Left: Apparatus as seen from Alice who is at rest with it. Right: Apparatus as seen from Bob who is moving relative to it.

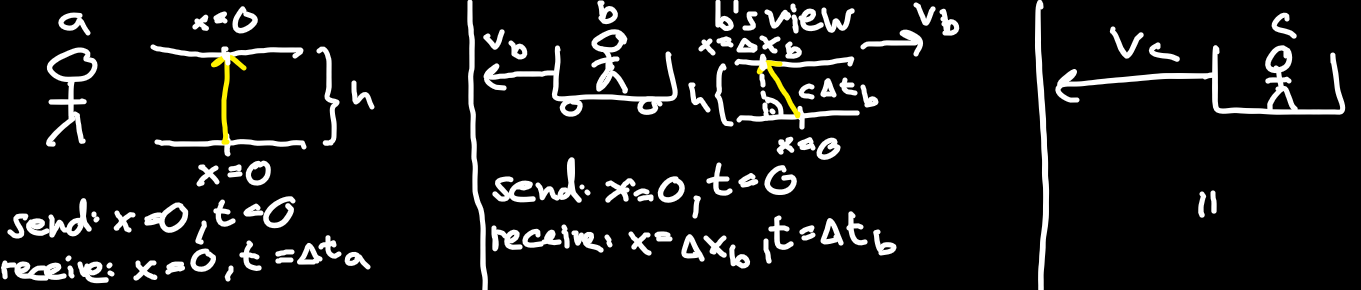

Setup and Alice

Consider Alice standing still on the ground with an apparatus as pictured in figure 6. The height of the apparatus is

Given the elapsed time we know that the distance the light moved must be equal to

Point of views and Bob's view

Introduce Bob on a train. From Alice's point of view the train is moving with constant velocity

How does the light in the aparatus look like from Bob's view? On sending, the light starts at horizontal coordinate

Let's look at the picture. Alice saw the light start and end at the coordinate

Invariant distance in Spacetime

A third person Charlie is also on a train, but moving at a different velocity

Solving Alice's, Bob's and Charlie's equations

All three right-hand sides must be equal. Does this look familiar? Think back to passive transformations. The coefficients of a vector expressed in a different coordinate basis might change, but the vector itself and its length does not change under passive transformations. This is exactly what happened here! There is a small but important difference in that they have a minus sign instead of a plus sign in front of the spatial offsets, so it is not just the ordinary euclidean distance we are dealing with here.

Note: Alice's part only appears to be missing because her spatial offset is zero (the light started and ended at the same horizontal coordinate).

In summary, all that happened was that the observers Alice, Bob and Charlie were using different coordinate systems, so the values they measured as expressed in their own coordinate systems did not match up, even though the thing they were measuring was fundamentally the same.

What we have discovered is the distance of spacetime that we can use to measure distance between spacetime events. With all three space dimensions it is

If this quantity is preserved, then this also implies that the usual euclidean distance in spacetime is not preserved.

Using this result we can now see what changes we need to make to our 4D algebra to arrive at the correct Spacetime Algebra.

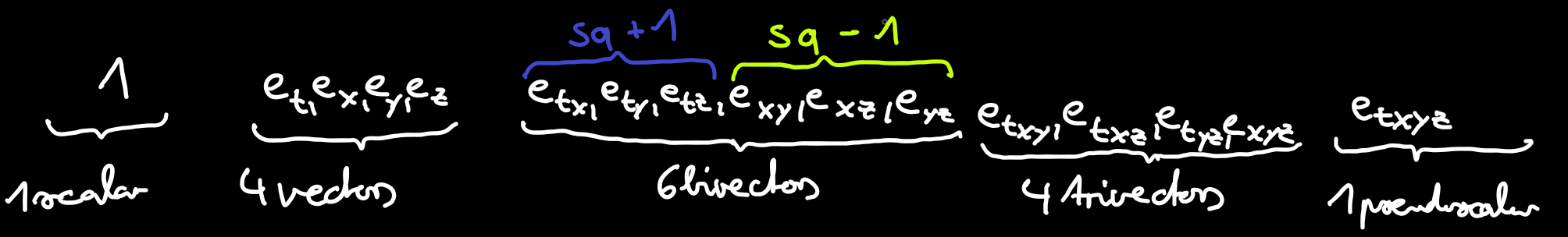

Spacetime Algebra

The only change we need to make is to the squares of our basis vectors. Having them all square to

This is usually refered to as the Spacetime Algebra. It has wide applications in physics and can be used to describe for example classical electromagnetics, most parts of the standard model of particle physics and, of course, relativity.

We can now verify that squaring a difference vector gives us the correct distance

Now we also have a justification for the factor of

In Geometric Algebra we are usually very interested in the bivectors as we can use them for building rotors that do interesting transformations which also easily compose. For example in ordinary Geometric Algebra the bivectors square to

Next we will take a look at a fundamental problem that relativity solves: the addition of velocities at speeds close to the speed of light. For this we will need to take a look at our bivectors squaring to

Conclusion

We started the section by looking at how we can express the paths objects take. We ended up with paths in spacetime parameterized by a parameter

We then saw that the points in spacetime are events containing both a space and time coordinate, and that we had to multiply our time component by the speed of light for the units to make sense.

After this we turned our attention to paths again and looked at different kinds of paths of objects in spacetime. Paths of objects at rest are straight lines in the

Finally we performed a thought experiment involving a light clock and different observers going at different velocities relative to it to uncover a distance metric for our spacetime. This led to the introduction of the Spacetime Algebra with

Formulas

- Path in spacetime:

- Path velocity:

- Path velocity of object at rest:

- Path parameterized by proper time:

- Spacetime distance / invariant interval:

- Spacetime Algebra:

Up next

Next we will look at a problem that arises when adding velocities close to the speed of light with ordinary addition, and we will see how the bivectors squaring to