Special Relativity with Geometric Algebra - Electromagnetism

Electromagnetism is most often described using Maxwell's equations in vector form. In Geometric Algebra these can be expressed as a single equation and a field that unifies the electric and magnetic fields. This also makes it very easy to combine our results from Special Relativity with Electromagnetism.

There are already a lot of resources showing how to do Electromagnetism with GA. Here are a couple of short ones that get the essence if you are interested:

- av8n article

- Last part of A Swift Introduction to Geometric Algebra by Sudgy

Because the magnetic bivector field is multiplied by the pseudoscalar

In the next part we will investigate an electric field as seen by an observer moving orthogonal to it.

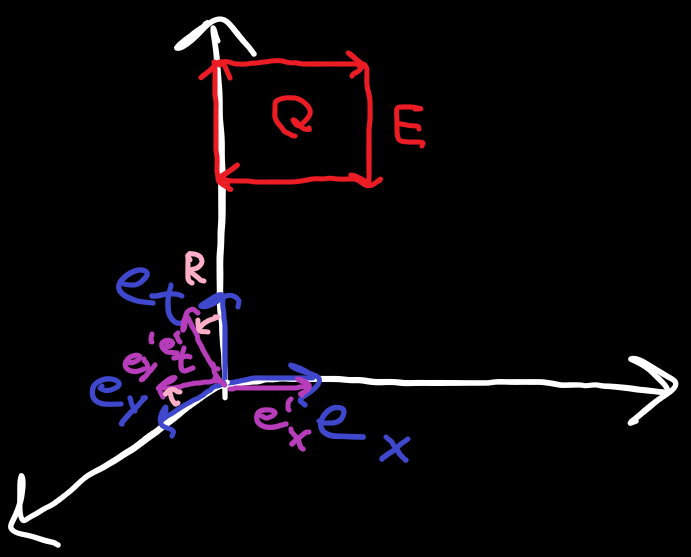

Electric field seen by observer moving orthogonal to it

Let's start with an electric field

The basis vectors for an observer moving relative to the field with rapidity

The rotor

Before continuing with the algebra, let's take another look at the diagram. What would we expect to happen if we applied the rotor to the field? The bivector field lies in the TX plane. The rotor (hyperbolically) rotates between the T and the Y axis. So we would expect the resulting bivector field to have not only have a TX component but also an XY component.

We can also see this visually: the original XY plane was orthogonal to

Reciprocal basis bivectors

Okay now for the algebra: because we are measuring bivectors and not vectors, we want to build reciprocal bivectors. For example to measure the XY component, we have a basis bivector

We already established that the moving observer should see a field in the TX and the XY plane, so let's build the reciprocal basis bivectors for those.

Field measured by orthogonally moving observer

Taking the inner product of the field with the reciprocal basis bivectors yields

We can see the the TX component of the field gets stronger the faster the observer moves in the Y direction (both positive and negative). We also have an XY component. If we look back to how

Conclusion

We saw that the electromagnetic field is described by the faraday bivector field